Why do I run?

Why does anyone?

I never really had an answer beyond ego before I trained for a Marathon, but I do remember my nephew asking me the same question during that winter training block, so I wrote this for him.

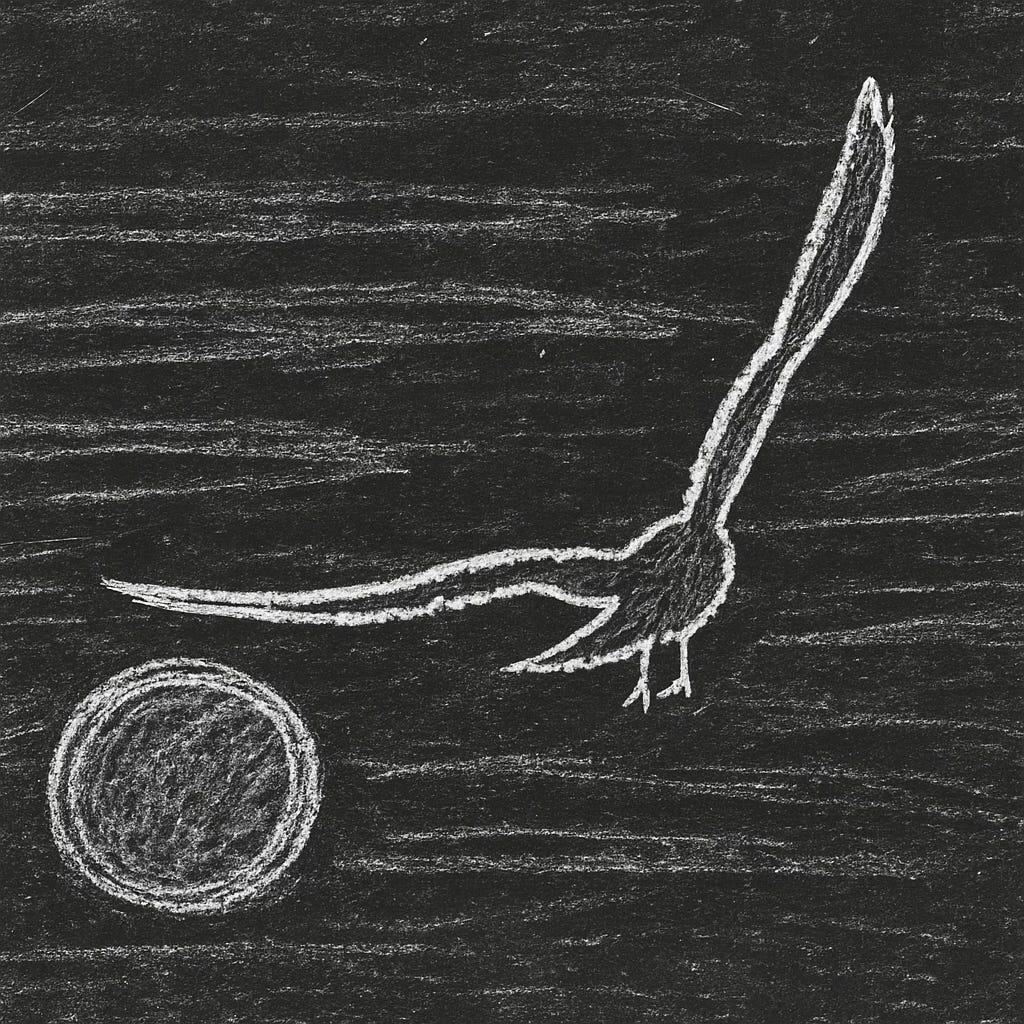

January, a typically bitter northern winter.

I paused mid step. Two days ago I looked up and watched the flight of a bird defy what we call gravity. It glided above the invisible tug at its leisure. I recognised it. Peculiar. Everything up there had begun to seem strange to me, all the more strange while I ran. My eyes gravitated upward most of the time, as their eyes seemed to survey below. I’d also begun to wonder if they take any notice of us, our habits, our activity, did they natter with their fellow flight-bearers at the end of a hard days flight and say; “You know today, I saw a human—”

Why do you run?

My nephew’s voice dissolved my reverie as I descended the stairs of my family home. He asked before he saw me. This question, he asked most days, and most days he was unsatisfied with my answer, he’d become too wise to believe anything I told him. Five years in existence was all he needed to know I had no real answer. I shrugged this time. He shrugged. He just wanted me to stay and play.

Today I ran for my own ego.

I don’t remember why I began running in the first place. Running, without a football or beyond the white lines of a football pitch never made sense to me; part of me still aligns with this. But, “I’ll be running”, I realised, was less insulting to a hearer than, “Sorry, I have plans today, tomorrow, the next day and the next day and you’re not invited!” Maybe that is the only reason I like marathon training… to avoid people. Escapology aside, I never ran because anyone I knew did, why would I care, I don’t run for fitness or joy either, so I also don’t understand followers of our socially acceptable construct presiding over the laws of - fitness. Whatever reasons people have, their tinfoil determination seemed false, as did their demonstrations of athleticism for virtual socials, whilst practicing none of the actual effort of… athleticism. Running in short, was always banal, people’s reasons always a lie, to me. But, and yet, I started one day, and my tinfoil determination remains strong.

Why are you running again?

He asked the same question for weeks, as inquisitive children often do. He was usually at my family home on Wednesdays and I happened to be here through winter. It had become a day for myself and this intrepid martian to converse, or play. I shrugged again. He shrugged. Then we laughed.

He watched me step through into the red tiled porch and close a door warped with glass. He ran toward the glass and pressed his cheek against it. I knelt and placed my hand against the glass, it was cooler than I expected but his merriment warmed it. He turned his wide smile toward me and waved. That wave seemed nonchalant and final. The gravity attached to it kept me still for a moment longer while he stared unblinking. I tied my laces wondering why I was emotionless everyday but today. I placed my headphones in, opened and closed the front door, and ran. I watched a bird fly over head, it was white, its wings still, it curved over my path. I recognised it.

Why don’t you stop running?

We were in the garden. Every week this curious whimsical child - happy as the moon when the earth eats the sun at night - asked a question. He grinned at his own cleverness. He was making a statement this time, you don’t know why you run, so stop. He also knew, if I stopped, we could continue to teach Bart gluttony in the back garden. My family home had a pond, and a gluttonous goldfish the size of a hotdog, with fins.

I carried him while he dropped more flakes onto the water’s surface, ensuring Bart (the fish) was fat enough to be boiled and thrown between medium slices of gluten free bread. I shrugged while holding him. A bird flew overhead. It was green, a small slick bird my stepfather liked to call ‘rare’. I recognised it. I felt his arms grow stiff and wrap around my neck. He was stronger than his dimpled face suggested. I plied him free and put him down. He ran inside. Again, my emotionless state was shuddering with this feeling of leaving. I walked through the house to where he stood before the glass door. Solid. Strong. His face a knot. I lifted him easily and reversed our positions then stepped backward beneath the door frame and closed the door between us. He sped to it and placed his head on the glass. I placed my cheek on it. I could see him smiling through his annoyance. I didn’t smile. I was leaving again.

Outside, I blocked these sensations with noise, and began running. I saw another bird, grey, small wings flapping, they stilled as it rode above, it flew perpendicular, sharing my lane.

You’re going running.

He said. A statement. A week had passed. He was sat tearing ham from between butter-less bread, he didn’t bother to get up, his eyes absorbed my sportswear with a petulant breath. He then ate the bread mechanically, without expression, hands lifting to mouth, mouth fulfilling its duty. I left without a farewell, without his face on the glass. I waited and looked in. He didn’t move.

Running.

That was all he said the week after. He stuck his tongue out. He no longer needed to understand. It was another pointless endeavour adults engage in, like work. Why work when you can play I heard him cogitate, why run when you can eat.

Outside, I saw a swarm of birds navigating invisible lanes. I watched them as I flew. They watched me as they ran together. Huh!?

What are you doing?

I was stretching, excitedly. I usually stretched before he arrived. But today he was early. He leapt aboard my downward dog position and proceeded to strangle me. Ask! I urged him without speaking, loosening his hold. Ask! He didn’t. By the time I’d finished he was leaping into the porch, velcro trainers fastened, ready to capture the hearts of his grandmother’s friends.

Are you getting big and strong?

This week he watched me doing a HIIT workout, I was running in the afternoon when he’d be gone. He mimicked some moves but his humorous nature turned press-ups into lounging, squats into bouncing like a gorilla and burpees into cushions spread over a dining room floor of volcanic lava.

You’re running.

I am. I replied, he shrugged and continued watching his cartoon. I waited, his attention didn’t. Hollow and embarrassed I left, he had no interest in this activity anymore.

The following week, he was somewhere else, I ran without his intervention, without his round dimpled face, without his mild infectious joy and intrepidity. He may never ask again, I surmised. He’d grown beyond caring, he saw running as a ludicrous activity that his uncle did for no apparent reason, only to leave, and exit, leave and exit, routinely leave and exit, as adults often do; the endeavour wasn’t important, only repetitive. I was part of this monotonous cycle without clear intention. But I could tell him why now, I ran because… wait, I don’t remember, why don’t remember! I looked up.

Why are you running again?

Two weeks had passed. He looked at me ever curious, his face and presence had matured, there was a gesture in his brow I hadn’t seen before. I knelt, before putting my trainers on and looked him in the eye. We were eye to eye, scholar and uncle - and I remembered, “I run because sometimes, the birds up there look down and say, “LOOK! LOOK! THAT HUMAN DOWN THERE IS FLYING!” He smiled, and swung his head up, eyes seeing through the ceiling. His smile widened, his eyes shone in a way that causes words to fade into tears and tears to stream into memory. Then he laughed. A new laugh I hadn’t heard.

Can you fly?

“Yes. Sometimes.” I said.

You can fly!?

I nodded.

He ran around the room.

I CAN FLY!

He was fast. I watched him dart from each end of the connecting rooms, while lacing up my trainers. I waved to him. He stopped at a distance. I stepped back into the porch and closed the glass door. He ran to the glass and placed his forehead to it, I placed my forehead to his. The glass warmed. I could see his breath. He smiled as if to say. Go fly, uncle.

That day I flew, they watched from above.